The Developing State: Representation in the English Parliament, 1365

For the first posts in this series, see here and here.

The development of a parliament comprised of both lords and commons was undoubtedly the greatest political and institutional development of fourteenth-century England. Parliament remained an occasion – it was not yet the regular institution it would become from the seventeenth century forward. However, in the words of the late, great Mark Ormrod “From the mid-fourteenth century onwards, the political success of the king depended to a large extent on his relations with parliament.”[1]

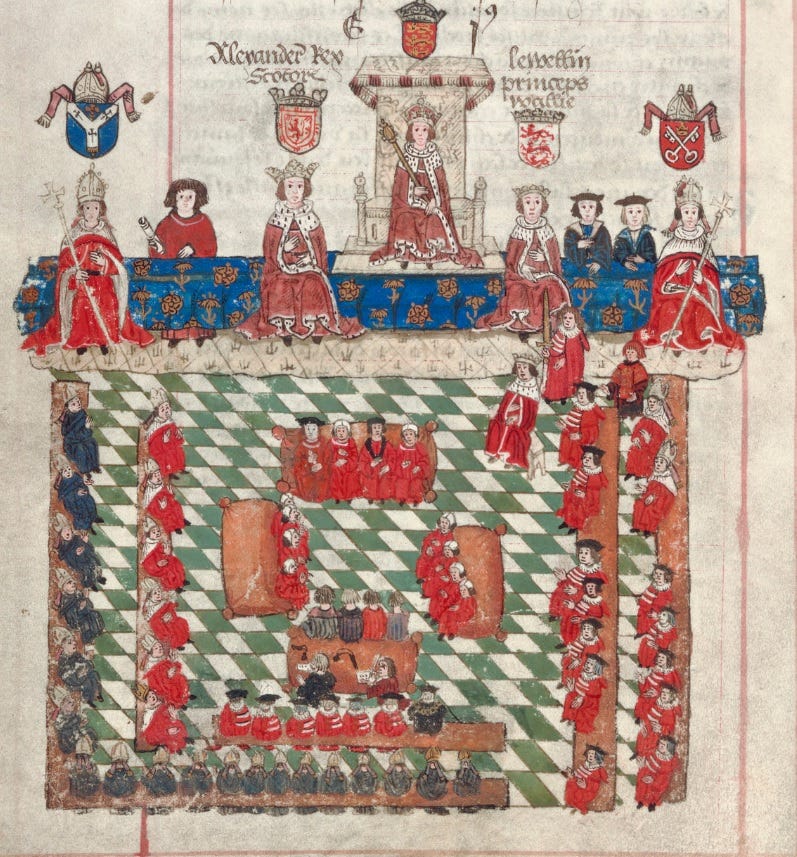

A sixteenth century illustration from the Wriothesley Garter Book, c. 1530 (https://www.rct.uk/collection/1047414/the-wriothesley-garter-book). This shows an imagined meeting of an English parliament from the reign of Edward III’s grandfather, Edward I, or Longshanks as Braveheart fans know him.

Much of this success must be credited to the king for most of the century, Edward III (r. 1327-77). Building on the parliamentary practices cultivated by his grandfather, Edward I (r. 1272-1307) and avoiding the appalling mistakes made by the decidedly unparliamentary rule of his father, Edward II (r. 1307-27), Edward III could be described as the king who finally made the relationship between crown and parliament function by establishing a partnership with its members and leading it as its president.[2] In future work I hope to show that, borrowing terminology from the study of the American presidency, Edward III operated at the nexus of politics and principles. He could be pragmatic and “rise above his principles” in a way his grandfather, Edward I, had found undignified to do so.[3] Of course, not all the credit belongs to the king. Edward cultivated a successful team of ministers and noble lieutenants who aided in his regime.

Edward III, it must be admitted, was not always the model parliamentary king. On occasion, he exhibited traits of autocratic leadership, similar to those observed in his grandfather and father. And if he partnered with parliament, it was not a partnership of equals. For most of his reign, Edward III retained the political initiative and was free to make up his mind without parliament. Yet it is also true that Edward III and his lieutenants “actively sought” to engage parliament in the great affairs of the realm. Many achievements can be credited to the Edwardian regime but the greatest for the English-speaking world is perhaps his honourable commitment to the “political principles of counsel and consent.” This made consensual politics a reality for medieval England and began to frame a form of parliamentary governance which is now practiced the world over.[4]

Edward III of England with his parliament from British Library Cotton Nero D. VI, f.72, which is a manuscript of the famous fourteenth century tract Modus Tenendi Parliamentum or “The Manner of Holding a Parliament.”

Having waxed lyrically over Edward III (if you cannot tell, I am something of an admirer of this king), let us get to the focus of this essay. For ruling in partnership with parliament would have amounted to little had parliament not been a binding force on the political community. This binding force was often assumed, especially in acts of war or statutory legislation, but it was not formally enunciated until late in Edward III’s reign in 1365.[5] The context was a legal case, but its implications were truly formative for the rest of English and much wider English-speaking history.

The case was one brought to the Court of Common Pleas (the court where civil suits were prosecuted).[6] It was based in a dispute between two prominent members of the English polity, Richard Fitzalan, earl of Arundel, and William Lenn, bishop of Chichester. The details of the suit need not concern us here. What matters is that the bishop during the dispute with Arundel had asked that the earl and one other be summoned to the papal court of Rome (based in Avignon, France at this time). This was in contravention of one of Edward III’s statutes and the king and his lawyers sued a writ against the bishop. To complicate business, a statute passed just the year before in 1364 asserted that anyone who so transferred a court case out of England had to come in his own person to defend himself, not by attorney. Bishop Lenn, however, had sent his attorney in his stead during the preliminaries of the case.

Here is where things get interesting. Before the Court in 1365, the bishop of Chichester’s attorney pleaded that the writ had been brought before the statute was made, and furthermore he knew of no such statute. Chief Justice Sir Robert Thorpe stated that the Court would consider both parties’ positions and adjourned proceedings to another day. When Court reconvened, Chichester’s attorney again stated that there was no statute made in 1364, and furthermore even if a statute was made, it was never widely published or proclaimed. To this, Chief Justice Thorpe answered:

Although proclamation was not made in the county, each one was bound to know it immediately when it was done in Parliament, because as soon as Parliament had concluded any matter, the law understood that each person had knowledge of this, because the Parliament represented the body of the whole realm, and for this reason it was not requisite to have a proclamation where the statute took its effect before.[7]

Chief Justice Thorpe concluded that parliament represented the entire realm of England. Everyone in the kingdom was presumed to be represented either in person in the lords – as a “peer of the realm” – or in the commons by an elected representative. No one could claim exemption from parliamentary statue because once enacted by the king with the assent of lords and commons, it was law.[8] The bishop’s attorney repeatedly tried to argue his client’s case, but to no avail. The Court found in favour of the king and against the bishop of Chichester.[9] Chief Justice Thorpe articulated what had been long acknowledged politically but not explicitly stated constitutionally. The concept of presumed parliamentary representation marked a significant development in the evolution of the English state. This fourteenth century precedent would be referred to repeatedly in the centuries which followed.

The significance of this proposition for later history, both positively and negatively, is evident. To take just one example, both perspectives of Chief Justice Thorpe’s assertion of parliamentary representation can be glimpsed exactly four hundred years later. The context was the debates surrounding the Stamp Act of 1765. This infamous act of parliamentary taxation was the spark that set off a long fuse which would result in the American Revolution. Parliament passed the Stamp Act in February 1765 with almost no debate. However, the reaction in British America was rapid and savage. The colonial assemblies condemned the Stamp Act, asserting their status as equals to the Westminster Parliament rather than subordinates. Only each colonial assembly, they argued, could legislate taxation for each colony. The colonists threw Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights back in the face of parliament: there could be no taxation of them by a body in which they were not represented.

George Grenville, prime minister of Great Britain, understood the point. However, he argued that while no colonial MPs sat at Westminster, the colonies were “virtually represented.” Stephen Conway argues that while this seems strange to modern ears, it had eighteenth century substance.[10] Many MPs whether as paid agents, merchants, or veterans of the Seven Years War or French and Indian War had dealings with the colonies and understood the colonial viewpoint. Grenville maintained that the American voice was heard in parliament. The American colonists, many rich oligarchs who now considered their rights under attack like previous generations of the English gentry, begged to differ.

In the Stamp Act, Chief Justice Thorpe’s spirit can be witnessed. His legal statement that everyone is presumed to be represented in parliament because “Parliament represented the body of the whole realm” justified Grenville’s notion of virtual representation. However, although everyone was theoretically represented in medieval English parliament, the colonists might argue that Thorpe would have emphasized the need for actual representation in practice. This parliamentary standoff allowed for no room for maneuver between the two camps. What was required, arguably, was an executive monarch who could mediate between the two strands of his subjects outside of parliament. Unfortunately, due to historical development and constitutional evolution, such was no longer a possibility in the eighteenth century as it once was in the fourteenth. George III was not Edward III.

[1] W. M. Ormrod, The Reign of Edward III: Crown and Political Society in England, 1327-1377 (London and New Haven, 1990), 200-1.

[2] For Edward I and his parliaments, see M. Prestwich, Edward I (London and New Haven, 1997), chapter 17. For detailed studies of Edward II’s failure in regard to parliament and other aspects of his reign, see G. Dodd, “Parliament and Political Legitimacy in the Reign of Edward II”, in The Reign of Edward II: New Perspectives, ed. G. Dodd and A. Musson (Woodbridge, 2006), 165-89; and S. Phillips, “Parliament in the Reign of Edward II, with Some After-Thoughts on the Modus Tenendi Parliamentum”, in FCE X, ed. G. Dodd (Woodbridge, 2018), 25-46.

[3] Dodd, “Parliament and Political Legitimacy”, 185 and n. 72.

[4] W. M. Ormrod, Edward III (London and New Haven, 2011), 371-2, 596-7, 599; J. S. Hamilton, The Plantagenets: History of a Dynasty (London, 2010), 226.

[5] A. Musson, “Second ‘English Justinian’ or Pragmatic Opportunist? A Re-Examination of the Legal Legislation of Edward III’s Reign”, in The Age of Edward III, ed. J. S. Bothwell (Woodbridge, 2001), 74-77.

[6] For much of what follows, see BU Law | Our Faculty | Scholarship | Legal History: The Year Books : Report #1365.027

[7] BU Law | Our Faculty | Scholarship | Legal History: The Year Books : Report #1365.027; YB 39 Edward III, 7. Also see Musson, “Second ‘English Justinian’”, 76; and G. L. Harriss, “The Management of Parliament”, in Henry V: The Practice of Kingship (Oxford, 1985), 137.

[8] Musson, “Second ‘English Justinian’”, 76 and n. 33.

[9] For the broader context of this case, see C. Given-Wilson, “The Bishop of Chichester and the Second Statute of Praemunire, 1365”, HR, 63 (1990), 128–42.

[10] S. Conway, “George Grenville”, in The Prime Ministers: Three Hundred Years of Political Leadership, ed. I. Dale (London, 2020), 44.