The Developing State: Durham Enters the House of Commons, 1673

This article begins a second series I will be working on in the future. As I have gone from high school to undergrad and finally to grad school, one interest which has stuck with me has been the idea of a developing state. Indeed, that is one reason I have been fascinated with studying England for so long. England was a united state early on (beginning in the tenth century) and gained increasing centralization as the centuries progressed. While I argue that most of the structures of English government were in place by the end of the fourteenth century, there would still be further development in the future. Today, I look at one development in the seventeenth century: the addition of the county of Durham to the House of Commons in 1673.

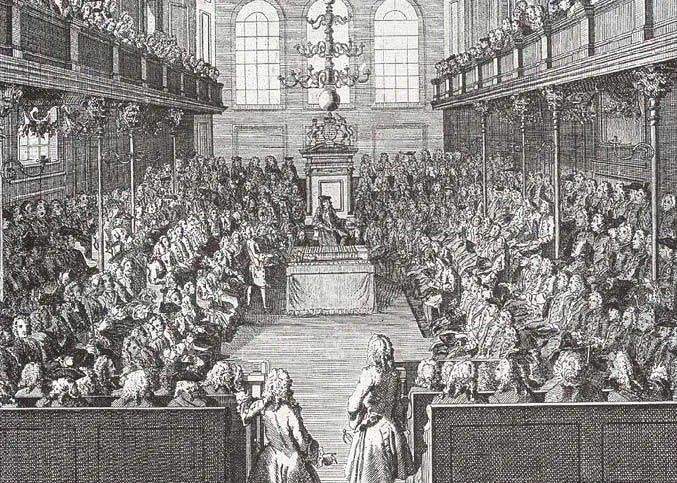

An engraving of the House of Commons in the later seventeenth century

The county of Durham for most of its history had been a palatinate. This meant it was a territory within which the king’s commands did not run. Rather, the bishop of Durham ruled it. He had charge of the raising of troops, minting of coins, and local justice within the palatinate.[1] When the English parliament began to develop from the thirteenth century forward, Durham also secured immunity from paying parliamentary taxes and, crucially for this study, sending representatives to parliament to sit in what would become the House of Commons. To the medieval mind, conscious of political boundaries, this was accepted. What is more surprising is that during the administrative shake-ups of the 1530s and 1540s, when England broke with Rome and remodeled much of its government, Durham still escaped sending members to the Commons.[2] It was not until 1673 that a bill for Durham to have its own MPs (Members of Parliament) in the Commons was read and approved in parliament.

Interestingly for such a political development, it made its impact with a whimper, not a bang. The main issue for the 1673 parliament was the Test Act. This legislation bared all those who would not profess loyalty to the king and faith in the Church of England from public office. The bill to accept parliamentary representatives from Durham by contrast was debated and passed over a series of sessions with no complaint and wide acceptance.[3] It was a political none issue. Yet it represented the end of a governing tradition stretching back to the eleventh century. And perhaps that is the point.

Sometimes we expect political changes to be earth moving. Speaking as an American, it may be that since our government was fashioned de novo within a four-month period in 1787, we expect all governments to be created at birth. England is the other side of that coin: a government that evolved over centuries and is still evolving today. The even greater aspect of this legacy is that England has been the model for incorporating changes within its older structures of government without those changes destabilizing the state itself. The incorporation of Durham into the parliamentary body of England is a minor change (hence the length of this article). But it represents a moment of progression in the creation of a more unified England as the eras roll by. Whether that is good in and of itself is debatable. That is certainly a question to have in mind as I reveal more of these moments in this series. Stay tuned.

[1] C. Liddy, The Bishopric of Durham in the Late Middle Ages: Lordship, Community and the Cult of St Cuthbert (Woodbridge, 2008) passim.

[2] C. S. L. Davies, “The Cromwellian Decade: Authority and Consent” TRHS 7 (1997), 186.

[3] Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 9, 1667-1687 (London, 1802), 259-60, 265-6, 269.