The Developing State

The Lord Advocate of Scotland, 1483

Having produced three pieces on the concept of Medieval Losers, it is high time I took a break and returned to an earlier series I have been working on, The Developing State. For the first, I looked at the incorporation of Durham into the House of Commons in 1673. Today, I go backwards in time and across the border to look at the development of the office of Lord Advocate of Scotland in 1483.

The first question immediately leaps out: who is the Lord Advocate of Scotland? A quick answer is that he or she is the equivalent of the Attorney-General of England and Wales or the Attorney-General of the United States. Like them, the Lord Advocate is the leading lawyer of the devolved Scottish government and represents the government in major cases. The current Lord Advocate is Dorothy Bain KC, (the second woman to hold the office). In 2022, she argued, unsuccessfully, the case for a second Scottish independence referendum before the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court in London.[1]

Rt Hon Dorothy Bain KC, the current Lord Advocate of Scotland. See Lord Advocate - gov.scot

The office of the Attorney-General in England and the Lord Advocate of Scotland do have similarities in terms of their creation. Unlike the Attorney-General of the United States, both the Attorney-General and Lord Advocate evolved over time. In England, from at least the thirteenth century, the crown appointed a king’s attorney to represent it in the two major courts, King’s Bench (mostly criminal cases) and Common Pleas (civil suits).[2] After the Yorkist usurpation of the English throne in 1461, the title “Attorney-General” gained traction and the office developed a political role as the advisor to the House of Lords in parliament.[3] The office of Lord Advocate also only commenced its development in Scotland in the second half of the fifteenth century. Yet, it commenced with a difference. The system of English common law was unique to England and had developed with only limited reference to older Roman law precepts. The Scottish system on the other hand owed more to Roman law in its development.[4] Additionally, Scottish law was a much less centralized legal system and made greater use of the local courts of the nobility and clergy. This owed to the nature of Scottish government. While medieval English government is often described as “self-government at the king’s command,” Scottish government was “self-government in the king’s name.”[5] Due to geography and the limited development of institutions, the Scottish crown needed to rely on local actors to make its rule effective.

However, during the fifteenth century, the Scottish legal system went through a major evolution. In 1426, James I (r. 1406-37) commissioned the sessions of council, “a specially constituted statutory judicial tribunal under parliamentary authority, with its own parliamentary judges, but wholly separate from the meetings of parliament.”[6] By the 1460s, the sessions emerged as the central apparatus for addressing the legal complaints of the king’s subjects.[7] From this development, the position of Lord Advocate would emerge.

The increasingly centralization of the Scottish legal and judicial system increased during the reign of one of the least successful Scottish kings, James III (r. 1460-88).[8] However, despite the problems of his reign, James is also one of the most interesting royal personalities to emerge from wider British history, and my candidate for the most unfairly maligned British monarch. Take that Richard III! One of the reasons for James’s unfair reputation, I believe, is the reception by later historians of his ambition to make Scotland a more integrated state on the models of England and, particularly, France. Building on the work of his father, James II (r. 1437-60), James sought to establish Edinburgh as the capital of Scotland and the center of royal government. One of his methods of doing so was via the law through the sessions of council. The sessions were reconstituted as the Lords of the Council in 1478.[9] The Lords sat in Edinburgh due to the presence of the king and the latter encouraged his subjects to appeal directly to the Lords rather than having first recourse to the local courts of the nobility and clergy. These developments would eventually culminate in the foundation of the College of Justice in 1532 during the reign of James V (r. 1513-42). One historian stated that James V was building upon a legacy first developed by his grandfather in the 1470s and 1480s.[10] One should note that James III’s motivations were not primarily selfless here: he wanted to extend the authority of the crown and discourage the use of the courts of the nobility, who he was often at loggerheads with. Nevertheless, it was a grand evolution in the experience of Scottish justice, and the Lord Advocate was part of it.

The first Lord Advocate emerged in the aftermath of the creation of the Lords of the Council. By 1483, the role solidified.[11] Its first holder was John Ross of Montgrenan, a knight from Ayrshire in southwest Scotland. Ross, apart from two of James’s chancellors, had the best record of any attendee as a Lord of the Council. Without any university background, Ross’s emergence was due to his closeness to James III.[12] His role extended far beyond the law. During the major rebellion which witnessed the end of James’s reign in 1488, Ross was the king’s closest councilor. In the three major military encounters during the rebellion, it was Ross who arrayed the king’s troops for battle while James played the symbolic and perhaps active role of warrior-king. Unfortunately for the king and his Lord Advocate, James “happinit to be slane” at the last engagement and Ross forced into exile.[13] In the eyes of the victorious rebels under James’s own son and heir, the new James IV (r. 1488-1513), Ross was persecuted as one of the chief evil councilors of the dead king. However, by 1490, due to the help of influential patrons and his own skills, Ross received a pardon and remerged as an attendee of parliament and one of James IV’s privy council.[14]

John Ross would not be the only Lord Advocate to find himself unpopular. The position was one of enforcing royal rights to the hilt as well as aiding in the Scottish legal system. And to state the obvious, the Lord Advocate was, well, a lawyer. James IV was likely the most popular king in Scottish history, but his Lord Advocate, Master James Henryson, was dubbed by the king’s biographer as “one of the most unpopular public figures of the reign.”[15] However, the position also attracted talent and proved an outlet for later influential political figures. The most powerful Scottish politician of the late eighteenth century, Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville, served as Lord Advocate of Scotland from 1775 to 1783 during the reign of George III and the administration of Lord North. Dundas’s nephew, Robert, later served in the role in the 1790s.[16]

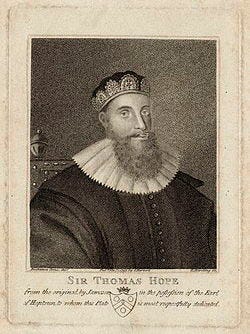

Sir Thomas Hope, 1st Baronet Hope of Craighall, Lord Advocate under Charles I (r. 1625-49)

Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville, Lord Advocate and Scotland’s most powerful politician in the late eighteenth century

By 1800, the Lord Advocate of Scotland, like his counterpart in England, had evolved into one of the most significant roles in government. This role demonstrates the link between the Middle Ages and the Digital Age. It is yet another indication that an understanding of medieval government and law is necessary to understand many of the complexities of the modern state in the Western world.

[1] IndyRef: Scotland's top lawyer Dorothy Bain publishes independence argument to Supreme Court | STV News

[2] During the Black Death in 1349, both king’s attorneys were part of the death rate that affected the government offices of the realm: W. M. Ormrod, “The English government and the Black Death of 1348-1349” in England in the Fourteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1985 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. W. M. Ormrod (Woodbridge, 1986), 178.

[3] E. Jones, “The Office of Attorney-General,” The Cambridge Law Journal 27 (1969), 43-53.

[4] The best work on the development of the Scottish state and law before 1300 is A. Taylor, The Shape of the State in Medieval Scotland, 1124–1290 (Oxford, 2016).

[5] A. Grant, “Fourteenth-Century Scotland,” in The New Cambridge Medieval History VI: c. 1300-c.1415, ed. M. Jones (Cambridge, 2000), 364.

[6] K. Stevenson, Power and Propaganda: Scotland, 1306-1488 (Edinburgh, 2014), 97.

[7] Stevenson, Power and Propaganda, 97.

[8] N. MacDougall, James III (Edinburgh, 2009) for James’s life and reign.

[9] MacDougall, James III, 363; Stevenson, Power and Propaganda, 113-5.

[10] MacDougall, James III, 363-4.

[11] Fifth Report of Session 2006-07: Constitutional Role of the Attorney General. House of Common Constitutional Affairs Committee. 19 July 2007, 145-6.

[12] MacDougall, James III, 361.

[13] MacDougall, James III, 338-9, 343, 345-7; N. MacDougall, James IV (Edinburgh, 1997), 32-3 and 42-4.

[14] MacDougall, James IV, 75, 80, and 82.

[15] MacDougall, James IV, 297.

[16] Fifth Report of Session 2006-07, 146.