Thomas Audley as Lord Chancellor

Thomas Audley, Baron Audley of Walden, was one of the preeminent servants of the English crown during the 1530s. Yet his name remains unknown compared to several of his close colleagues: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, St Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, and Richard Rich, Baron Rich of Leez. In part this may be due to Audley’s personality, as will be seen. But it also may have been because Audley always seemed to remain below the high political radar, quietly effective in the background. And as this survey of his career will demonstrate, raising one’s head above the parapet in Henry VIII’s England was not a wise move.

Thomas Audley was an Essex boy, born and bred in Earls Colne. Most sources cite his birthdate as around the year 1488, just three years into the new Tudor dynasty’s usurpation of the English throne.[1] Like many boys from rising yeomen and gentry families, Audley decided to embark on a legal career to advance himself. He settled into the Inns of Court – the set of four schools which trained lawyers in the England of 1500 – and would eventually graduate from the Inner Temple in 1526. Along the way, he had already entered local politics, having served as a burgess, town clerk, and even a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Essex city of Colchester. Although Audley was already thirty-eight in 1526, his career was just beginning. From 1526 to 1531 he served as Attorney-General of the Duchy of Lancaster, the chief estate of the crown and an organization near and dear to my heart. It was his appointment as Speaker of the House of Commons in 1529, however, which would see Audley rise to the top of Tudor politics. [2]

Audley took up the Speakership at the beginning of one of the most monumental parliaments in all of English history. This was the Reformation Parliament, which would sit through multiple sessions from 1529 to 1536. As Speaker, Audley was required to manage the Commons on behalf of the king and his ministers. But he also had to represent the Commons to the king. And Henry VIII was never an easy man to please. Arguably Audley’s chief role in the Reformation Parliament was as an intervening agent in the Supplication of the Clergy to Henry VIII in the 1532 session.[3] This central piece of legislation was the first link in the chain which would eventually lead to Henry VIII’s assumption of the title of Supreme Head on Earth of the Church of England in 1534. The Supplication was also too much for the current Lord Chancellor of England, Sir Thomas More. On More’s resignation, Henry VIII, likely on the advice of his emerging chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, granted custody of the Lord Chancellor’s most significant attribute, the Great Seal of England, to Thomas Audley. Audley thereby became the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. In January 1533, he was confirmed as Lord Chancellor of England, a post he would hold for the next eleven years.[4]

To understand the significance of this appointment, it is necessary to give a bit of background on the office of Lord Chancellor of England. The Chancellorship reached back to the distant medieval past. By the fourteenth century, the Chancellor had emerged as the king’s senior minister. He presided over the Chancery, the largest administrative department of the English state, which was the king’s writing office. All official documents were issued by the Chancery under the king’s Great Seal. The Chancellor also sat as the head of the king’s administrative council when the king himself was not present. In the same manner, as the Chancery acquired authority as an equity court of law, the Chancellor presided over it as judge.[5] The legal role of the Chancellor had grown exponentially, as can be seen by the career of Henry VIII’s first great minister, Lord Chancellor Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. This was the office now conferred upon Thomas Audley in the new year of 1533.

Audley’s Chancellorship was certainly an eventful one. As Lord Chancellor, he was head of the English legal system. This led to him being present, whether presiding or not, at the trials of such notable figures as Thomas More and Anne Boleyn. In addition, it seems he and one of his proteges, the future Lord Chancellor Richard Rich, were the two main proponents of the massed Dissolution of the Monasteries that took place from 1536 forward. This role, highlighted by historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, revised the historical consensus that Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, was the agent behind the Dissolution.[6] Despite this difference of opinion, Audley and Cromwell continued to have a close working relationship and indeed friendship throughout the 1530s. This close relationship was reflected in both men being named as evil ministers by the rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, the largest rebellion faced by Henry VIII during his reign.[7] Audley and Cromwell survived the rebellion, with Audley going on to be rewarded with a peerage as Baron Audley of Walden in 1538 and membership within the prestigious Order of the Garter in 1540. Walden was the former Saffron Walden Abbey in Audley’s home county of Essex. This exemplifies how much Audley himself profited from the Dissolution. Audley demonstrated this urge for land and property throughout his career in royal service. This gives an indication that his personality admitted of several weaknesses. There are other indications as well.[8]

Despite his friendship with Cromwell, Audley certainly did nothing to prevent his fall in 1540. Likewise, it is improbable that he was unaware that the charges against both Thomas More and Anne Boleyn were in the first case dubious and in the second trumped up. Nevertheless, he presided over More’s trial and acted in his capacity as Lord Chancellor during Anne’s. He does not seem to have shown much sympathy for the thousands of religious lives that the policy of Dissolution wrecked, and instead used it as an opportunity to profit himself and his family. Given this, how should we characterize Audley? A loyal servant of the king who never fell foul of his murderous rage? Or a political trimmer who always made sure he was on the right side? A measured view is that he was both. Audley was a loyal servant to his king. Many English monarchs would have relished having a Lord Chancellor as talented and innovative as Audley proved to be. Henry VIII certainly rewarded him for the trouble he took in his behalf. Yet, Audley was careful to never be more than professional in his relationship with the king. Wolsey, More, and Cromwell all made the mistake of becoming too close to the king, and when his love turned to loathing all three paid the price. By avoiding the king’s rage and playing the part of the loyal, apolitical servant of the state, Audley died full of years in his bed.

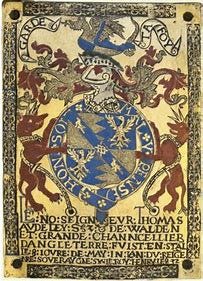

Thomas Audley’s coat of arms, adopted by the College of St Mary Magdalene

Beyond politics, Audley left another, brighter legacy. When he received the former Walden Abbey, Audley inherited its connection with Buckingham College, Cambridge. In 1542 Audley reestablished the college as the College of St Mary Magdalene. The college took on his coat of arms as its own and Audley ordained in the new statutes of the college that he and his heirs should be visitors to the college for all time, a role his descendants kept until 2012. Two years later, in failing health, he resigned the Chancellorship and died nine days later. He was buried in the church of St Mary the Virgin in Saffron Walden, near his seat at Walden Abbey. A recent post by the researcher Kirsten Claiden-Yardley analysed Audley’s tomb within the church. Fascinatingly for a Tudor nobleman, the tomb contains no mention of family or faith. It displays Audley’s arms with the Garter circling them and celebrates him as Henry VIII’s lord chancellor and loyal servant.[9] That is how Audley and his family wanted him remembered: a devoted servant of his king who acquired his barony in diligent work at the king’s behest. That diligent work was not always pure, but that is politics. Thomas Audley helped administer the changes which transformed England in the 1530s and died in his bed. Few of the close colleagues who worked with him in effecting those changes died in a comparable manner. That is a legacy in and of itself.

[1] For a fuller biography of Audley’s life than this profile, see L. L. Ford, “Audley, Thomas, Baron Audley of Walden (1487/8-1544)” in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography or ODNB. For a more accessible glance, see Thomas Audley, Baron Audley, Lord Chancellor of England” in Encyclopedia Britannica.

[2] R. Somerville, History of the Duchy of Lancaster Vol. I: 1265-1603 (London, 1953), 407.

[3] D. MacCulloch, Thomas Cromwell: A Life (London and New York, 2018), 163-4.

[4] MacCulloch, Thomas Cromwell, 165 and 168.

[5] W. M. Ormrod, The Reign of Edward III: Crown and Political Society in England, 1327-1377 (London and New Haven, 1990), 70 and 77.

[6] MacCulloch, Thomas Cromwell, 202 and 320-2.

[7] Ibid, 393-4 and 400.

[8] Ibid, 197 and 478-9.

[9] Tomb: Thomas Lord Audley – Kirsten Claiden-Yardley (kclaidenyardley.com)