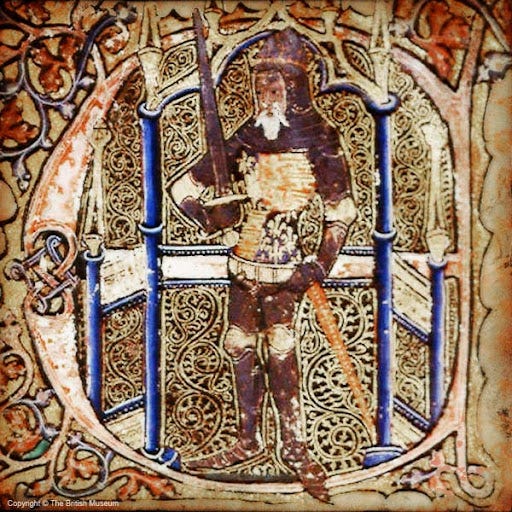

Edward III, armoured to defy all challenges, come what may. From BL MS Cotton Nero D. VI, f. 4

In the summer of 1340, Edward III faced obstacles on every front. After a spectacular piece of political theatre when he claimed the crown of France in January, he rushed home to England from the war front in the Low Countries. The preliminary stages of what would come to be the Hundred Years War had stalled and the king needed more money and material to pursue the struggle with France. Throughout the spring and the summer, the king met with his ministers and then his parliament. Through political concessions – many of which were initially against his better judgement – Edward secured a tax and began raising troops and ships. A massive French fleet was assembling off the Flemish coast and the king was going to have to cut his way through them to return to his allies to mount a new campaign against Philip VI of France.[1]

It was while Edward was organizing his fleet and forces at Orwell in Suffolk that he was visited by his chief minister, John Stratford, archbishop of Canterbury and chancellor of England. Whether in a commandeered manor house or perhaps in a royal pavilion[2], Archbishop Stratford came to offer his counsel to his monarch. The king had not raised enough forces to confront his French adversary; the campaign should be delayed until more could be mustered so they king would be sure to succeed in his endeavors. Unlike many of his royal contemporaries, Edward III was receptive to counsel and understood its importance in government. At this moment, however, with his vision of kingship in jeopardy, the king had no time for his chief minister to oppose his designs. His frustration flared so much so that the archbishop supposedly resigned as chancellor in protest. After the archbishop’s departure, Edward summoned both the admiral and lieutenant of his eastern fleet to get their military advice. The admiral and his lieutenant were forced to admit they agreed with the archbishops’ prognostications. Edward III, like his Plantagenet forbears, was possessed of a fierce temper. Unlike several of them, he often kept in check, but he now exploded on his officials:

“I will cross the sea in spite of you. You, who are afraid when there is nothing to be frightened of, can stay at home.”

Such at least was the scene as recounted by the chronicler Robert of Avesbury.[3] As with all chronicle sources of the Middle Ages, it is hard to be sure how much of the account is true and how much is “imagined histrionics.”[4] Yet, having studied Edward III on and off for the better part of twenty years, the scene rings true to me. Edward’s chief biographer, the late great Mark Ormrod, believed the episode demonstrated how the king’s sulking attitude and refusal to recognize the sage advice of his ministers revealed how little he considered how his policies in 1340 were stretching his administration to the breaking point. Indeed, the king’s next homecoming in November 1340 would lead to one of the biggest crises of his reign.[5]

As always, Ormrod’s view commands respect – no man knew Edward III and the sources of his reign better. However, Edward’s response to his military subordinates demonstrates to me the king’s courage, resolution, and defiance of the odds. If one of Edward’s greatest attributes as king was his willingness to avail himself of the good advice of others, another was his ability to sometimes take decisive action over their objections and win the day.[6] This case was yet another example. Edward and his fleet did sail. They confronted the superior French fleet in the Battle of Sluys and won one of the greatest English military victories of the Hundred Years War.[7]

It was in Edward’s character to challenge the odds. In a letter to the doge of Genoa the next year, after yet more stumbles in his war strategy, he wrote:

“My power has not been laid so low and the hand of God is not yet so weak that I cannot with his grace prevail over my enemy.”[8]

As I mentioned in my first article on the characteristics of medieval kingship, there are certain qualities that medieval rulers needed to have to be successful. Three such characteristics of Edward III’s own kingly demeanour come through in these exchanges: his courage, his basic if sincere faith in God and himself, and his “belief in his own destiny.”[9] It was his determination that he was down but not yet out that allowed him to recover from his mistakes in 1340-1 and go on to triumph against France, taking England to the greatest apogee yet witnessed in its long history. In other words, he rose to the occasion. And that folks is what great leaders do, medieval or modern.

[1] W. M. Ormrod, Edward III (London and New Haven, 2011), 212-20.

[2] Edward was not averse to sleeping in pavilions or tents in his own realm. In fact, he did so into his mid-fifties: Ormrod, Edward III, 462, citing TNA E101/396/2, fol. 42v.

[3] Robert of Avesbury, De gestis mirabilibus regis Edwardi Tertii, ed. E. M. Thompson (RS,1889), 311, citied by Ormrod, Edward III, 220.

[4] Ormrod, Edward III, 221.

[5] Ormrod, Edward III, 221.

[6] Ormrod, Edward III, 92 and 484.

[7] Ormrod, Edward III, 222-4; J. Sumption, Hundred Years War I: Trial by Battle (Philadelphia, 1990), 325-9.

[8] Foedera II.ii, 1156, cited by J. Sumption, Edward III: A Heroic Failure (London and New York, 2016), 47.

[9] Ormrod, Edward III, 599.

Edward III's brash confidence in the face of his ministers' caution reminds me of similar episodes from the life of Alexander the Great. Parmenion is always presenting a voice of caution to balance the temerity of his dauntless king.